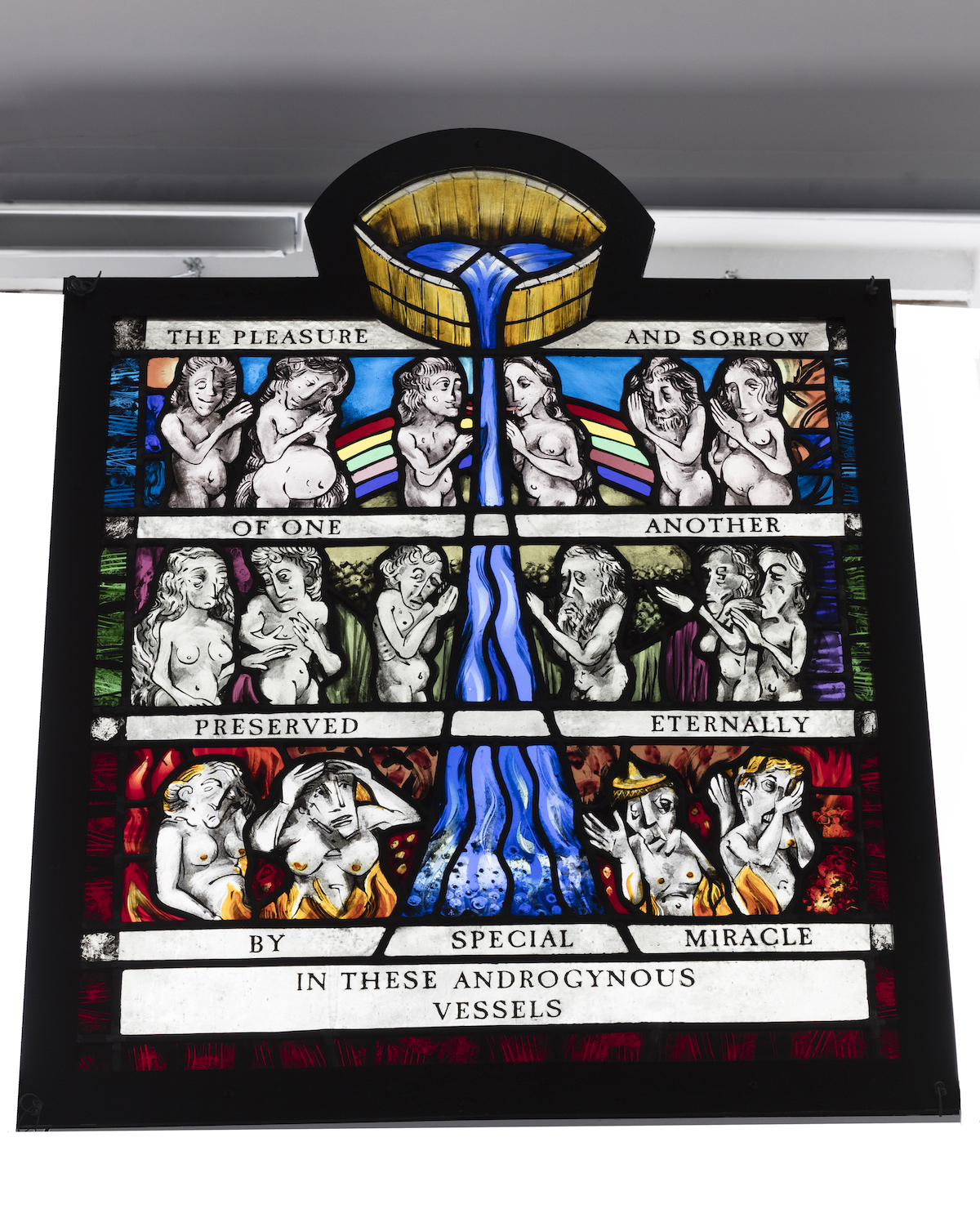

Video Installation, ink drawings, stained glass

9:16 HD

Full running time - 21min loop

Viewing copy on request

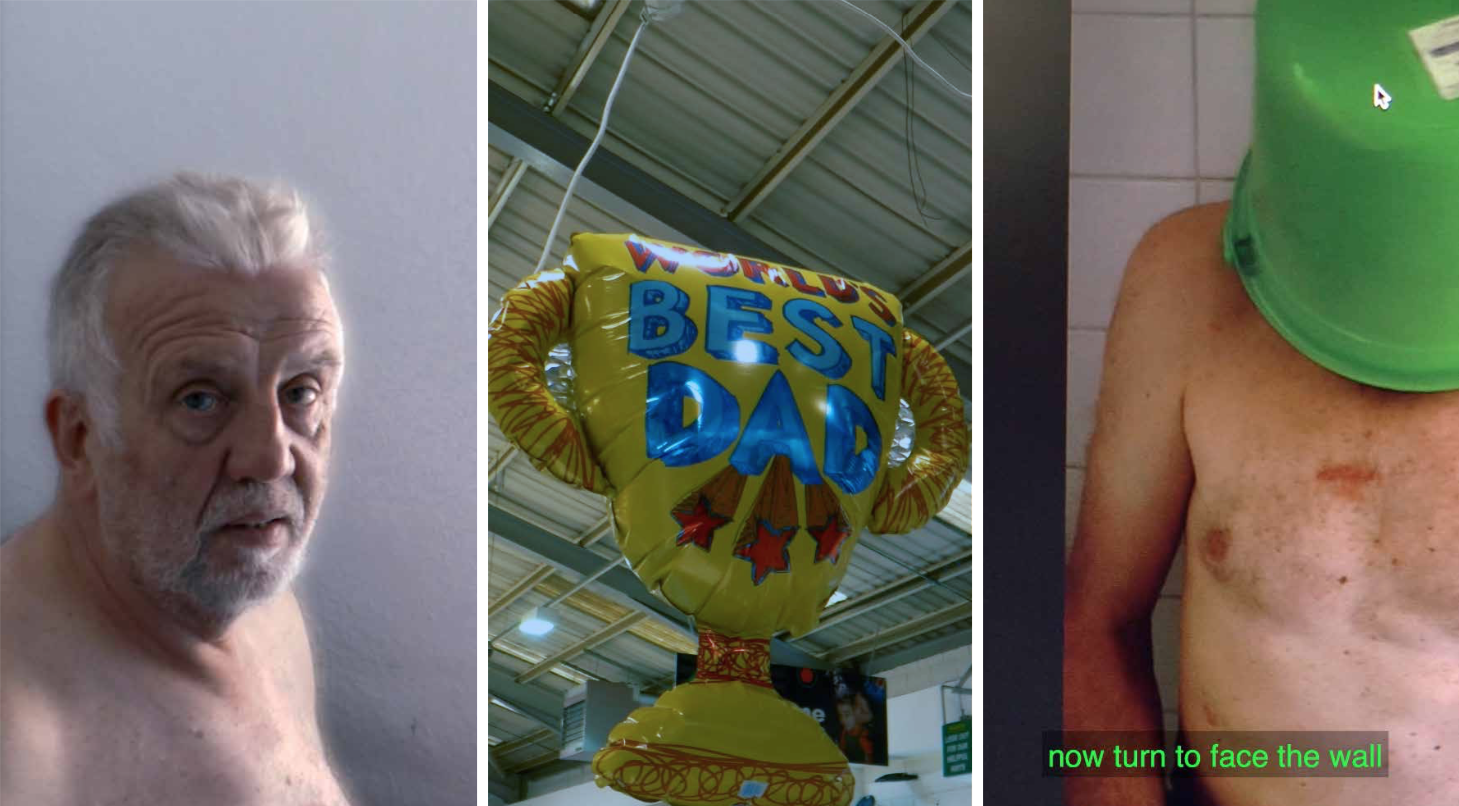

Excerpt

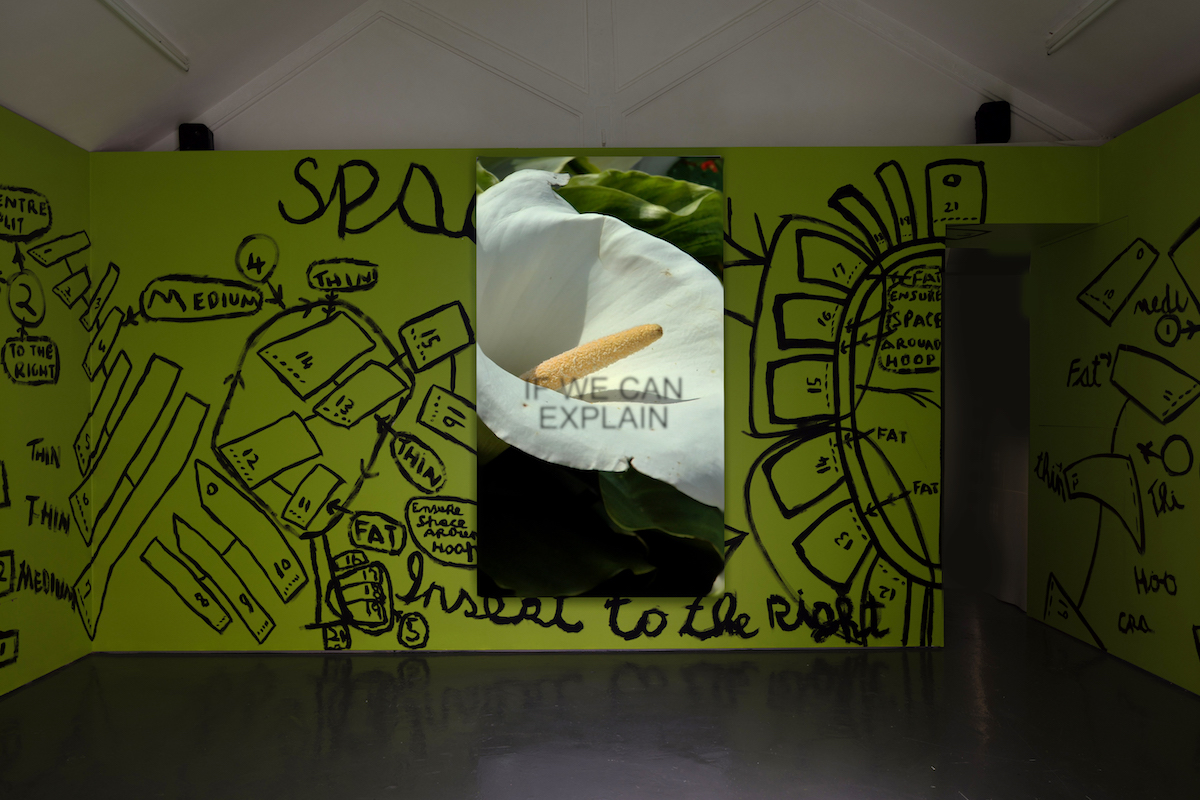

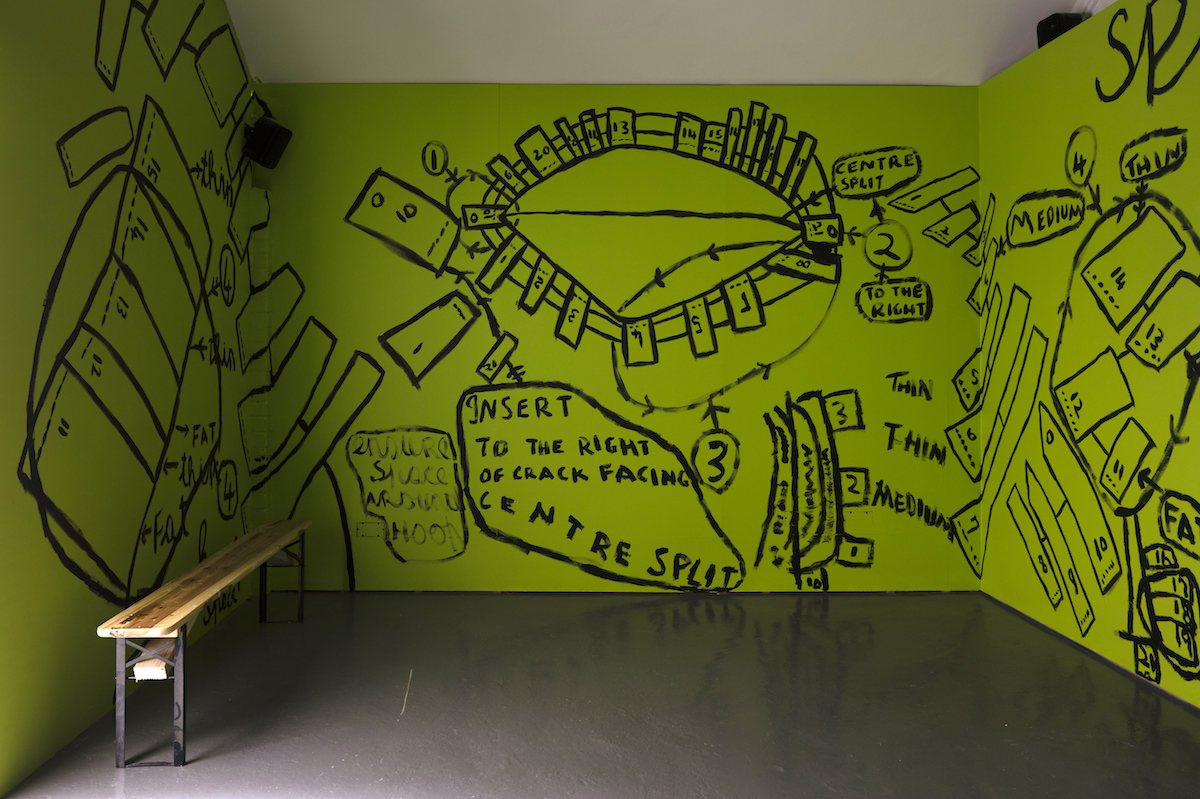

Installation views

Intimacy is a promise, a kind of economy and debt. Like any other contractual obligation it comes with subclauses as well as written, spoken, and often imagined terms and conditions. It rarely, if ever, comes with a warranty or a health and safety form, which would save more than one of us from the bitter pill of unfulfilled expectation and a history of STDs. In as much as a contract suggests a kind of agreement or settlement, an intimate exchange includes the potential for hesitation or misunderstanding. When one agrees to be intimate with another, one accepts that such bumps are part of the contract; a small, at times large, deposit to be paid in hope of a greater reward. Although it can be consensual and mutually sought, the virtual contract of intimacy might also be acquired or passed on, like a will or inheritance. The already encoded family unit, for instance, enacts a forceful contract amongst its member’s bodies via blood cells, DNA histories and chemical imbalances.

The possibility of intimacy by contract is most clearly represented in the figures of the analyst and the analysand within the psychoanalytical situation, something explored by Leo Bersani and Adam Philips in their co- authored book Intimacies. In the first chapter of the book, intimacy –within psychoanalysis– is considered as built from the ‘gift’ of knowledge, from the patient, in exchange for understanding, facilitated by the analyst. Acknowledging the lack of equal footing between both parties, the book imagines how a similar type of engagement might survive outside the psychoanalytical paradigm, as “an original device to start two people on the way to intimacy, to thwart their intimacy, and finally to allow them to drop the analytic conceit and to be intimate” (Bersani, 2008, p.11). Further, Philips’ definition of psychoanalysis as “what two people can say to each other if they agree not to have sex” sets the conditions that would allow for an intimate relation founded on agreement and contractual binding. Without it, intimacy risks the blurry ground between desire and need, projection and reality.

Cut it off at the trunk, considers how an intimate exchange between himself and his father might be facilitated through the contract of art production and its multifaceted modes of permission and display. From this premise, he seeks to probe the positions, cultural inscriptions and power dynamics embedded in the erotics of the father and son relationship.

Throughout the exhibition, the image of the bucket –both object and metaphor– recurs as a device that enables moments of unity and division. Painted directly on a wall, a diagram outlines the steps of construction to build this bucket. The task’s realisation –one that seems to have been previously performed, built and dismantled, with the bucket now in parts hanging meticulously on a wall– is loaded with a certain level of choreographed libidinal masculinity, coded within a warranted system of physical connection. Here, one imagines it as a kind of bonding exercise between Ryan and his father, “man to man, step by step”, as instructed by the seller of the bucket during a conversation that appears typed in Ryan’s new 9:16 film that takes the exhibition’s title. In the film, banal intimacies and aggressions both performed and consented open up questions that defy emotional, sexual and generational norms; “I want to piss on him”, reads a subtitle that is sometimes used to embody Ryan’s voice but mostly that of his therapist who imparts commentary as diagnosis. The desire is at once both real and imagined –too perverse to enact but too gratifying to ignore.

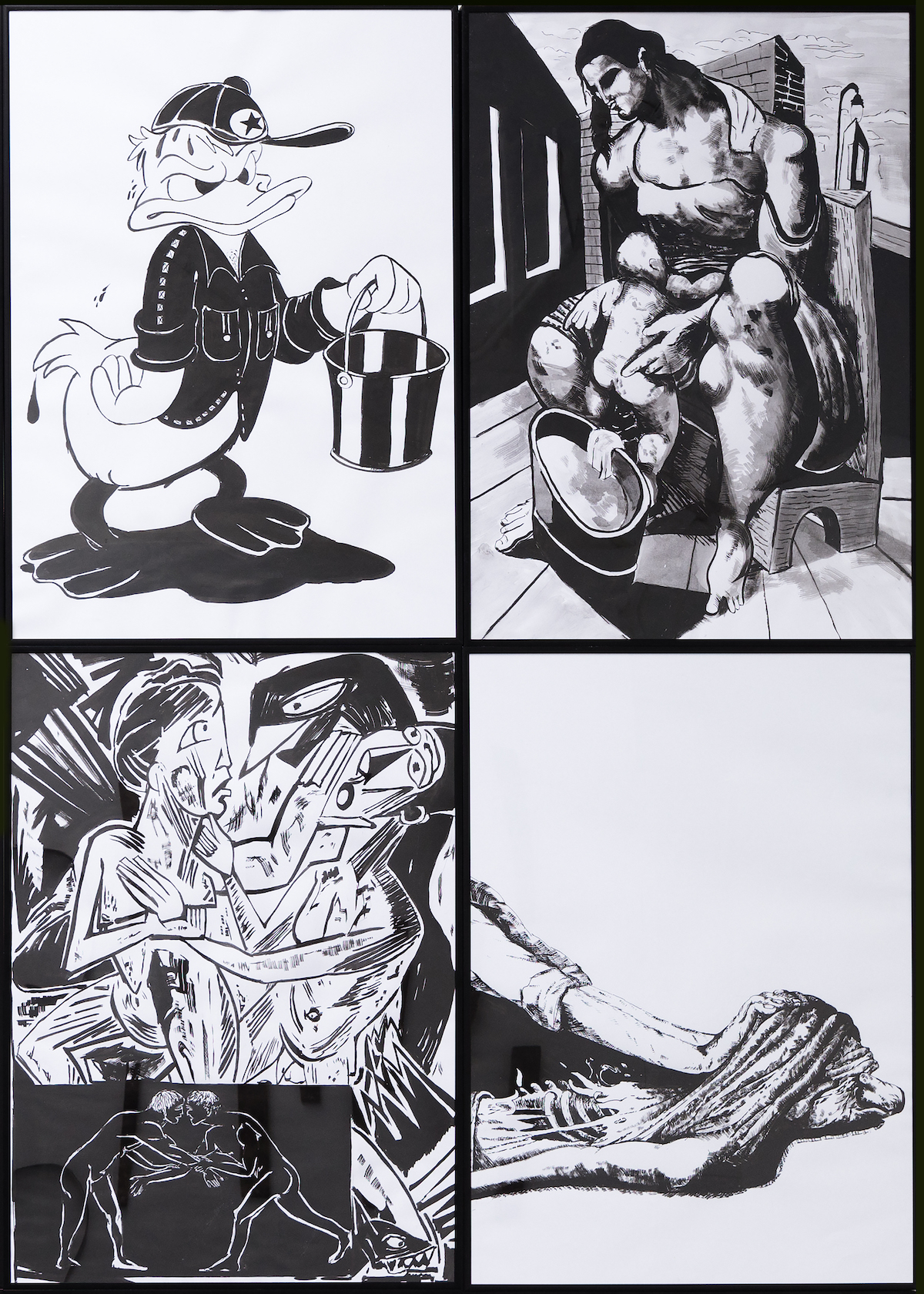

Just as the bucket facilitates a site of connection and mutual understanding, a series of graphic black and white ink drawings open a visual space of convergence between Ryan’s and his father’s disparate subjectivities. The imagery –seemingly sourced from a variety of contexts, physical and virtual– contrasts and exposes different forms of pain, suffering and shame, toying with the possibilities of their iterations of both violence and pleasure. A drawing of doubtful Thomas fingering Jesus’ wound appears alongside a diagram of an erection pump; a soft teddy dressed in tight leather gear is ‘knifed’ from its back and is pictured dead, yet, of course, was never actually alive; a rather unhappy-looking Donald Duck holds an empty bucket, the contents of which seem to have been poured on him, perhaps by him, as part of a sick joke or hazing ritual. As if trying to digest his and his father’s divergent definitions of desire, Ryan commits to paper imagery that is both arousing and disturbing, alarming and reassuring, as a way of speaking and feeling freely what might otherwise be left unsaid.

If Ryan’s attempt to create intimacy with his father is both a private and public act mediated by the contract of making and presenting work, his father’s agreement to partake in such processes is based on equal investment in the forms through which their connection can be enacted. What is compelling about this is Ryan’s father’s understanding of the systems of display associated with the production and distribution of Ryan’s work, and thus his desire to be a part of them, complicit in their making. Having created up the environment for intimacy to flourish –an act akin to “consensual sex” as Ryan’s therapist describes it– one is left to wonder how far that is actually possible, beyond and in spite of their mutual agreement.

Excerpt from essay by Eliel Jones

Documentation courtesy of Rowing, London